When the first men’s wristwatches were produced, the wire lugs that were soldered onto cases were quite thin because no one expected that these watches would be used for anything beyond light activity. However, when America entered the war, it quickly became evident that something thicker would be needed to withstand the rigors of the battlefield. Nevertheless, cases with thin lugs were the style most readily available by the major case manufacturers of the time: Illinois Watch Case Company, Fahys, Wadsworth, and others. Thus, the majority of trench watches that you will encounter will have these thin lugs. Notice, also, the oversized, knurled winding crowns. This was a deliberate design element to help soldiers wind their watches with cold, or even gloved, hands.

|

| Typical case design of a WWI trench watch |

Probably by the middle of the war and certainly toward the end, the fragile nature of these cases had become evident, and manufacturer were making cases with meatier lugs.

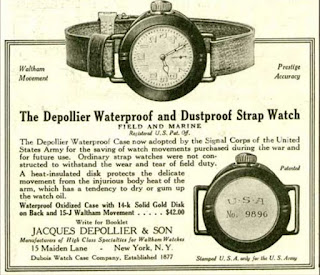

Another major problem with early watch case designs is that they were not very resistant to the elements. Dirt, moisture, sweat, and mud would often seep through the case and into the movement, causing it to stop. Several manufacturers invented various solutions to deal with this, but probably the most famous was Charles Depollier, of the Depollier Watch Case Co. of Brooklyn, NY.

|

| Advertisement for the field and marine watch featuring the Depollier Waterproof/Dustproof case, and Waltham movement. |

|

| An actual specimen of the watch |

Depollier’s case contained a screwdown bezel and back, combined with a screwdown crown to seal all the entry points. The back even had an extra plate of solid 14kt gold, supposedly to protect the movement from excess body heat. A bit of overkill in my opinion, but it was a great selling point at the time. The resulting Depollier Waterproof Watch Case was probably the finest example of wrist hardware that a soldier could wear at the time. Depollier partnered with the Waltham Watch Co. to make the complete watch, and it was a very successful venture. The watches with the Depollier case were available to soldiers as early as 1917. Many were contracted by the U.S. military, and many more were bought by soldiers and officers out of their own wallets. Some say the Depollier waterproof case was the inspiration for the Oyster case, made famous by Rolex a decade later. Today, trench watches housed in the Depollier Waterproof cases are some of the most desired by collectors. They are hard to find, and priced in the thousands of dollars. It is doubly rare to find one with the original solid gold back plate, as many of these were pried out of their cases and sold for scrap.

Crystal Guards

Next, we move on to crystal guards. From the earliest days of pocket watches, it quickly became clear that the crystal – made of glass -- was the most vulnerable point of a watch. Cracked or shattered, it left the dial and hands wide open to damage, not to mention dirt, moisture and glass fragments getting into the movement and damaging it. A couple of solutions for wristwatches were offered early on. The first was a case design with cutout coverings of one form or another that partially protected the crystal.

A couple of problems arose with this solution. One, these cases tended to be expensive and, two, many of covers nearly obscured the dial to the point of not being able to tell the time. So a second solution came along in the form of shields that could be snap fit over the top of an open case, and thus the crystal guard was born.

As you can see, they came in a host of designs, and again some covered the crystal so much as become a hindrance in viewing the time. But they did a good job of preventing crystals from being broken or shattered from bumps or hitting the ground from a soldier literally having to hit the dirt.

Somewhere along the 1980s, some collectors and dealers started calling these inventions “shrapnel guards,” probably because it sounds more sexy than crystal guards. But they were never called shrapnel guards, and the very idea that these covers would protect the watch from shrapnel is ridiculous. But the myth persists, legitimized by collectors guides which use the term. Trust me, it’s wrong. I’ve seen about 30 original ads for these devices, and they were NEVER referred to as shrapnel guards.

By the way, beware of modern counterfeits on these. The real ones will almost always have a patent mark and/or patent date stamped into the back.

Bands.

As you have seen in many of prior images, early watch bands, or straps, were narrow strips of leather or canvas that looped through the wire lugs of a watch. This was fine for motoring or horseback riding, but it was evident that something more substantial was needed for the rigors of the battlefield. Numerous designs were introduced, probably the most famous was the Kitchener watch strap.

Not only was it more sturdy, but it allowed for leather to sit against the wrist rather than the metal of back of the watch, which was ultimately more comfortable and absorbed sweat. Just as an aside, I find it amusing that this style briefly came back into vogue in 1970s in the form of the “Hercules Watch Band.”

So in the short span of two years, from 1917 to when the Great War ended in 1919, the wristwatch had undergone a fairly radical redesign, from somewhat feminine to something fairly macho. Look at the difference:

During the war, and right after, watch cases would undergo the next step in their evolution through a design where the lugs were fully incorporated into the case and were not soldered onto the case. And so we have the full formation of the modern wristwatch as we more or less know it today.

But I would say the vast majority of watches worn during the Great War were of the wire lug variety. You might wonder how many watches the military ordered during the war. We don’t really have any records that have survived, at least not that we’ve found, but surely it was in the tens of thousands. To give you an idea, here’s a picture that’s been seen often on the Internet of one jewelry store that bought up a bunch of surplus watches after the war.

Wouldn’t you like to have bought up a bunch of these watches at four bucks apiece? And straps for 10 cents apiece? And these watches are probably those that were issued by the government. Many other service men – particularly officers – who weren’t issued a watch often bought their own in fancier – gold and silver – cases.

The war’s end drastically changed the way the wristwatch was advertised and perceived by the public. Even though pocket watches continued to dominate the market until the early 1930s, the wristwatch was now solidly a masculine item. Here’s one of my favorite ads:

|

| Image by watchophilia.com |

What to look for when buying a trench watch

Let’s spend a few paragraphs summarizing what to look for when considering a trench watch purchase

- Originality or at least replacement parts correct to the age of the watch. This especially includes the movement, which should have a serial number corresponding to the war years. Crystals should be glass, not plastic. Crowns should be correct to the period. Crystal guards, if present, should be genuine and fit snugly to the watch.

- Engraving is good! Many watch collectors do not like personal engraving on the backs of their watches. But trench watch collectors LOVE engraving, particularly if a name is combined with a date and/or military unit. It helps immensely to authenticate the watch as a true trench watch that saw actual military service, as opposed to a civilian specimen. It’s important to remember that these trench-style watches were available to the general public as well as military personnel, though it’s correct to call either a “trench watch.”

- Mechanical condition. Watch movement should wind and set smoothly, with no “grinding,” or “skipping,” indicating worn parts. Accuracy is not a huge concern to most collectors, but the watch should keep time to at least within 2 min/day.

- Manufacturers. Most trench watch collectors seem to focus on U.S. brands, and particularly Waltham and Elgin. But to the best of my knowledge, all U.S. manufacturers made trench watches. Not all U.S. manufacturers, however, contracted with the U.S. military. But as was pointed out in #2, “trench watch” refers to a style of watch, not necessarily whether the watch saw actual service or not. So watches by Illiinois, Hampden, and Hamilton from the 1917-1919 period could rightly be called trench watches as well. Things get a little more dicey on the Swiss side. We know that companies such as Omega, Tavannes, Longines, and more made watches that served on both sides of the battle … the Allies, and the Central Powers. But this is an area which, to my knowledge, has not been well documented. So if this collectors’ niche is of interest to you, proceed with caution. I’ve seen watches for sale/auction on eBay, for example, that are CLEARLY ladies’ wristlet watches, but are being offered as “trench watches.” Proceed with caution. Seek help from fellow collectors on trusted and well respected Internet forums.

Finally, I want to show you a couple of pictures of current production watches to show you how incredibly practical the design of the wristwatch was nearly a century ago.

Look familiar? These current production watches draw heavily of the design elements of a century ago, and they look completely up to date!

That’s the end of my series on trench watches, and I hope you have found my stories informative. If you have enjoyed this work, please leave a positive comment!